This video is directly relate to our blog, the main theme of our blog is

"accouting",The video is produced from the school hall,During the editing

process, comparing with two editing tools we found that Imovie was relative ease

of use, since we merely need to add our video source into the software, and then

selected one title from the module board.

By dragging the segments to finish

the cutting and combining. In addition, as the Imovie version looks impressive

and vivid, most of group members voted for this version rather than the movie

maker version.

At last, we inserted background music and words to display

the video perfectly.

Sunday, May 27, 2012

report

The first difficult of making this video is that, some of

our group members became shy when we record the video, so we have to practice

again and again, and record the same part of video several times until every

people in our group is satisfy.

Another challenges

and tribulations of this assignment were mainly brought about by our lack of

previous video editing experience, specifically in regards to figuring out how

to cut out certain parts of the video, and saving it in a format readable by

each group member’s computer. Nevertheless, we managed to overcome these

adversities fairly quickly through unification of ideas and trial and error

using Windows Live Movie Maker.

tribulation

we had some difficulty with was time management and being able to get together

to film and edit the video. Since we wanted everyone to be included in the

filming of the video, we decided the best time to film would be during a

practical class, and edit in our own time after that. Fortunately however, we

were able to come to an agreement as to when most group members would be able

to do specific parts of the assignment, which helped the entire process run as

smoothly as possible.

Sunday, May 6, 2012

Accounting System

Organized set of manual and computerized accounting methods, procedures, and controls established to gather, record, classify, analyze, summarize, interpret, and present accurate and timely financial data for management decisions.

Components of the Accounting System:

Think of the accounting system as a wheel whose hub is the general ledger (G/L).

Feeding the hub information are the spokes of the wheel. These include

-

- Accounts receivable

- Accounts payable

- Order entry

- Inventory control

- Cost accounting

- Payroll

- Fixed assets accounting

National Carbon Accounting System

Australia’s National Carbon Accounting System (NCAS) provides world-leading accounting for greenhouse gas emissions from land based activities.

Land based emissions (sources) and removals (sinks) of greenhouse gases form a major part of Australia’s emissions profile. Around 24 per cent of Australia’s human-induced greenhouse gas emissions come from activities such as livestock and crop production, land clearing and forestry.

Land management such as soil preparation, fertiliser use, harvesting and

burning all affect emissions of greenhouse gases. A significant proportion of

Australia’s land based emissions occur as non-carbon dioxide gases, in

particular methane from livestock production and nitrous oxide from fertiliser

application.

These modules are ledgers themselves. We call them subledgers. Each contains the detailed entries of its specific field, such as accounts receivable. The subledgers summarize the entries, then send the summary up to the general ledger. For example, each day the receivables subledger records all credit sales and payments received. The transactions net together then go up to the G/L to increase or decrease A/R, increase cash and decrease inventory.

We'll always check to be sure that the balance of the subledger exactly equals the account balance for that subledger account in the G/L. If it doesn't, then there's a problem.

Read more: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/accounting-system.html#ixzz1u8Tyx0Dm

Types of Accounting

Financial accounting is the field of accountancy concerned with the preparation of financial statements for decision makers, such as stockholders, suppliers, banks, employees, government agencies, owners, and other stakeholders. Financial capital maintenance can be measured in either nominal monetary units or units of constant purchasing power. The fundamental need for financial accounting is to reduce principal–agent problem by measuring and monitoring agents' performance and reporting the results to interested users.

Financial accountancy is used to prepare accounting information for people outside the organization or not involved in the day-to-day running of the company. Management accounting provides accounting information to help managers make decisions to manage the business.

In short, financial accounting is the process of summarizing financial data taken from an organization's accounting records and publishing in the form of annual (or more frequent) reports for the benefit of people outside the organization.

Financial accountancy is governed by both local and international accounting standards.

Management accounting or managerial accounting is concerned with the provisions and use of accounting information to managers within organizations, to provide them with the basis to make informed business decisions that will allow them to be better equipped in their management and control functions.

In contrast to financial accountancy information, management accounting information is:

Financial accountancy is used to prepare accounting information for people outside the organization or not involved in the day-to-day running of the company. Management accounting provides accounting information to help managers make decisions to manage the business.

In short, financial accounting is the process of summarizing financial data taken from an organization's accounting records and publishing in the form of annual (or more frequent) reports for the benefit of people outside the organization.

Financial accountancy is governed by both local and international accounting standards.

Management accounting or managerial accounting is concerned with the provisions and use of accounting information to managers within organizations, to provide them with the basis to make informed business decisions that will allow them to be better equipped in their management and control functions.

In contrast to financial accountancy information, management accounting information is:

- primarily forward-looking, instead of historical;

- model based with a degree of abstraction to support decision making generically, instead of case based;

- designed and intended for use by managers within the organization, instead of being intended for use by shareholders, creditors, and public regulators

- usually confidential and used by management, instead of publicly reported;

- computed by reference to the needs of managers, often using management information systems, instead of by reference to general financial accounting standards.

Accounting for Non-current asset

NON-CURRENT ASSETS

Noncurrent assets are cleverly defined as anything not classified as a current asset. The main line items in this section are long-term investments; property, plant, and equipment (PP&E); and goodwill and other intangible assets.

Long-Term Investments. This is money invested in either bonds with longer terms than one year or the stock of other companies. These aren't as liquid as cash and short-term investments, and prices may fluctuate, so it's possible that the value shown on the balance sheet may be too high or too low. If it's a big enough balance, you may want to dig into the details to make sure you're comfortable with the kinds of risks the firm is taking with shareholders' money.

Property, Plant, and Equipment (PP&E). These assets represent the bricks and mortar of a company: land, buildings, factories, furniture, equipment, and so forth. The PP&E amount on the balance sheet is typically reported net of accumulated depreciation--the total amount of depreciation recorded against the assets over their life. Eventually, PP&E has to be replaced, and depreciation is a company's best estimate of these "replacement" costs from wear and tear. Keep in mind that PP&E is usually not a very accurate measure of what a firm's bricks and mortar are really worth. Many times, buildings worth millions of dollars are reported at next to nothing in PP&E because of accumulated depreciation. Likewise, the actual value of a company's land--which is recorded in PP&E at its acquisition price--may be worth exponentially more than what is recorded.

Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets. Intangibles are, just as the name describes, assets that can't be touched and are generally not going to turn into cash. The most common form of intangible assets is goodwill. Goodwill is formed when one company buys another and pays more than the target company is worth (as defined by the net worth, or equity on the target's balance sheet).

You should view this line item with high levels of skepticism because most companies tend to pay too much when making acquisitions. Therefore, the value of goodwill that shows up on the balance sheet is often higher than what the intangible assets are really worth. Accounting rules require companies to value goodwill every year, and if a company lowers the value of the goodwill it records--a phenomenon known as impairment--it's a tacit admission that the company paid too much for an acquisition it made in the past.

Depreciation

Definition of 'Depreciation'

1. A method of allocating the cost of a tangible asset over its useful life. Businesses depreciate long-term assets for both tax and accounting purposes.

2. A decrease in an asset’s value caused by unfavorable market conditions.

Investopedia explains 'Depreciation'

1. For accounting purposes, depreciation indicates how much of an asset’s value has been used up. For tax purposes, businesses can deduct the cost of the tangible assets they purchase as business expenses; however, businesses must depreciate these assets in accordance with IRS rules about how and when the deduction may be taken based on what the asset is and how long it will last.

Depreciation is used in accounting to try to match the expense of an asset to the income that the asset helps the company earn. For example, if a company buys a piece of equipment for $1 million and expects it to have a useful life of 10 years, it will be depreciated over 10 years. Every accounting year, the company will expense $100,000 (assuming straight-line depreciation), which will be matched with the money that the equipment helps to make each year.

2. Currency and real estate are two examples of assets that can depreciate or lose value. During the infamous Russian ruble crisis in 1998, the ruble lost 25% of its value in one day. During the housing crisis of 2008, homeowners in the hardest-hit areas, such as Las Vegas, saw the value of their homes depreciate by as much as 50%.

Cash control

Cash control is a process that is utilized to verify the complete nature and accurate recording of all cash that is received as well as any cash disbursements that take place. As a broad principle of responsible financial accounting, cash control takes place in any environment where goods and services are bought and sold. As such, businesses, non-profit organizations and households all employ the basic tenets of cash control.

To fully understand cash control, it is helpful to understand what is meant by cash, when it comes to financial accounting. Along with referring to currency and coin, cash is also understood to include forms of financial exchange like money orders, credit card receipts, and checks. Essentially, any type of financial exchange that can be immediately negotiated for a fixed value qualifies as cash.

Cash control means competently managing all these types of financial instruments by maintaining an accurate tracking system that accounts for both receiving and disbursing the cash. Designing a cash control process is not difficult at all. There are a few basic elements that will be incorporated into the process regardless of whether the cash control procedure is used in the home or in an office or business environment.

First, all transactions related to cash must be documented and recorded immediately. With cash control, there is no use of the accrual method of accounting. Each cash receipt is recorded upon reception, while each disbursement is entered at the time that the payment is released. The mode of documentation requires only some basic template that will record the necessary data. For the home, a checking account can be used to track all cash deposited into a common account for the good of the home, with the check book register can serve as the basic document that keeps track of the inbound and outbound transactions.

Next, solid cash control procedures requires that there be only certain individuals who have access to the cash. This type of security serves two purposes. First, accountability is established for the way that the cash is managed. Second, the empowerment of two people to oversee cash control helps to ensure that important transactions can take place at any given time, even if one individual is unavailable for some reason.

Last, cash control demands that the documents related to the task are kept separated from the physical location of the cash. In other words, the accounting book that is used to record the cash transactions should not be kept in the safe with the currency, money orders, and checks. This simple precaution helps to ensure that the task of altering the physical evidence related to cash in hand is more difficult and thus minimizes the chances for theft to occur.

Saturday, May 5, 2012

cost accounting

cost-volume-profit analysis

Cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis expands the use of information provided by breakeven analysis. A critical part of CVP analysis is the point where total revenues equal total costs (both fixed and variable costs). At this breakeven point (BEP), a company will experience no income or loss. This BEP can be an initial examination that precedes more detailed CVP analyses.

Cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis expands the use of information provided by breakeven analysis. A critical part of CVP analysis is the point where total revenues equal total costs (both fixed and variable costs). At this breakeven point (BEP), a company will experience no income or loss. This BEP can be an initial examination that precedes more detailed CVP analyses.

Cost-volume-profit analysis employs the same basic assumptions as in breakeven analysis. The assumptions underlying CVP analysis are:

- The behavior of both costs and revenues in linear throughout the relevant range of activity. (This assumption precludes the concept of volume discounts on either purchased materials or sales.)

- Costs can be classified accurately as either fixed or variable.

- Changes in activity are the only factors that affect costs.

- All units produced are sold (there is no ending finished goods inventory).

- When a company sells more than one type of product, the sales mix (the ratio of each product to total sales) will remain constant.

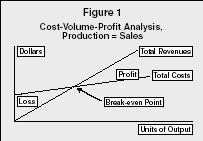

Figure 1

Figure 1

Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis, Production = Sales

In the following discussion, only one product will be assumed. Finding the breakeven point is the initial step in CVP, since it is critical to know whether sales at a given level will at least cover the relevant costs. The breakeven point can be determined with a mathematical equation, using contribution margin, or from a CVP graph. Begin by observing the CVP graph in Figure 1, where the number of units produced equals the number of units sold. This figure illustrates the basic CVP case. Total revenues are zero when output is zero, but grow linearly with each unit sold. However, total costs have a positive base even at zero output, because fixed costs will be incurred even if no units are produced. Such costs may include dedicated equipment or other components of fixed costs. It is important to remember that fixed costs include costs of every kind, including fixed sales salaries, fixed office rent, and fixed equipment depreciation of all types. Variable costs also include all types of variable costs: selling, administrative, and production. Sometimes, the focus is on production to the point where it is easy to overlook that all costs must be classified as either fixed or variable, not merely product costs.

Where the total revenue line intersects the total costs line, breakeven occurs. By drawing a vertical line from this point to the units of output (X) axis, one can determine the number of units to break even. A horizontal line drawn from the intersection to the dollars (Y) axis would reveal the total revenues and total costs at the breakeven point. For units sold above the breakeven point, the total revenue line continues to climb above the total cost line and the company enjoys a profit. For units sold below the breakeven point, the company suffers a loss.

Illustrating the use of a mathematical equation to calculate the BEP requires the assumption of representative numbers. Assume that a company has total annual fixed cost of $480,000 and that variable costs of all kinds are found to be $6 per unit. If each unit sells for $10, then each unit exceeds the specific variable costs that it causes by $4. This $4 amount is known as the unit contribution margin. This means that each unit sold contributes $4 to cover the fixed costs. In this intuitive example, 120,000 units must be produced and sold in order to break even. To express this in a mathematical equation, consider the following abbreviated income statement:

Unit Sales = Total Variable Costs + Total Fixed Costs + Net Income

Inserting the assumed numbers and letting X equal the number of units to break even:

$10.00X = $6.00X + $480,000 + 0

Note that net income is set at zero, the breakeven point. Solving this algebraically provides the same intuitive answer as above, and also the shortcut formula for the contribution margin technique:

Fixed Costs ÷ Unit Contribution Margin = Breakeven Point in Units

$480,000 ÷ $4.00 = 120,000 units

If the breakeven point in sales dollars is desired, use of the contribution margin ratio is helpful. The contribution margin ratio can be calculated as follows:

Unit Contribution Margin ÷ Unit Sales Price = Contribution Margin Ratio

$4.00 ÷ $10.00 = 40%

To determine the breakeven point in sales dollars, use the following mathematical equation:

Total Fixed Costs ÷ Contribution Margin Ratio = Breakeven Point in Sales Dollars

$480,000 ÷ 40% = $1,200,000

The margin of safety is the amount by which the actual level of sales exceeds the breakeven level of sales. This can be expressed in units of output or in dollars. For example, if sales are expected to be 121,000 units, the margin of safety is 1,000 units over breakeven, or $4,000 in profits before tax.

A useful extension of knowing breakeven data is the prediction of target income. If a company with the cost structure described above wishes to earn a target income of $100,000 before taxes, consider the condensed income statement below. Let X = the number of units to be sold to produce the desired target income:

Target Net Income = Required Sales Dollars − Variable Costs − Fixed Costs

$100,000 = $10.00X − $6.00X − $480,000

Solving the above equation finds that 145,000 units must be produced and sold in order for the company to earn a target net income of $100,000 before considering the effect of income taxes.

A manager must ensure that profitability is within the realm of possibility for the company, given its level of capacity. If the company has the ability to produce 100 units in an 8-hour shift, but the breakeven point for the year occurs at 120,000 units, then it appears impossible for the company to profit from this product. At best, they can produce 109,500 units, working three 8-hour shifts, 365 days per year (3 X 100 X 365). Before abandoning the product, the manager should investigate several strategies:

- Examine the pricing of the product. Customers may be willing to pay more than the price assumed in the CVP analysis. However, this option may not be available in a highly competitive market.

- If there are multiple products, then examine the allocation of fixed costs for reasonableness. If some of the assigned costs would be incurred even in the absence of this product, it may be reasonable to reconsider the product without including such costs.

- Variable material costs may be reduced through contractual volume purchases per year.

- Other variable costs (e.g., labor and utilities) may improve by changing the process. Changing the process may decrease variable costs, but increase fixed costs. For example, state-of-the-art technology may process units at a lower per-unit cost, but the fixed cost (typically, depreciation expense) can offset this advantage. Flexible analyses that explore more than one type of process are particularly useful in justifying capital budgeting decisions. Spreadsheets have long been used to facilitate such decision-making.

Unsold production is carried on the books as finished goods inventory. From a financial statement perspective, the costs of production on these units are deferred into the next year by being reclassified as assets. The risk is that these units will not be salable in the next year due to obsolescence or deterioration.

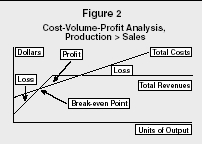

Figure 2

Figure 2

Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis, Production > Sales

While the assumptions employ determinate estimates of costs, historical data can be used to develop appropriate probability distributions for stochastic analysis. The restaurant industry, for example, generally considers a 15 percent variation to be "accurate."

APPLICATIONS

While this type of analysis is typical for manufacturing firms, it also is appropriate for other types of industries. In addition to the restaurant industry, CVP has been used in decision-making for nuclear versus gas- or coal-fired energy generation. Some of the more important costs in the analysis are projected discount rates and increasing governmental regulation. At a more down-to-earth level is the prospective purchase of high quality compost for use on golf courses in the Carolinas. Greens managers tend to balk at the necessity of high (fixed) cost equipment necessary for uniform spreadability and maintenance, even if the (variable) cost of the compost is reasonable. Interestingly, one of the unacceptably high fixed costs of this compost is the smell, which is not adaptable to CVP analysis.

Even in the highly regulated banking industry, CVP has been useful in pricing decisions. The market for banking services is based on two primary categories. First is the price-sensitive group. In the 1990s leading banks tended to increase fees on small, otherwise unprofitable accounts. As smaller account holders have departed, operating costs for these banks have decreased due to fewer accounts; those that remain pay for their keep. The second category is the maturity-based group. Responses to changes in rates paid for certificates of deposit are inherently delayed by the maturity date. Important increases in fixed costs for banks include computer technology and the employment of skilled analysts to segment the markets for study.

Even entities without a profit goal find CVP useful. Governmental agencies use the analysis to determine the level of service appropriate for projected revenues. Nonprofit agencies, increasingly stipulating fees for service, can explore fee-pricing options; in many cases, the recipients are especially price-sensitive due to income or health concerns. The agency can use CVP to explore the options for efficient allocation of resources.

Project feasibility studies frequently use CVP as a preliminary analysis. Such major undertakings as real estate/construction ventures have used this technique to explore pricing, lender choice, and project scope options.

Cost-volume-profit analysis is a simple but flexible tool for exploring potential profit based on cost strategies and pricing decisions. While it may not provide detailed analysis, it can prevent "do-nothing" management paralysis by providing insight on an overview basis.

management accounting

Management accounting is a methodology employed by a company’s senior management team to extract business-critical data, such as that regarding the firm’s financial position, so that vital day-to-day operational decisions can be made. Also called managerial accounting, this process typically requires department managers to create various reports and present that information to the senior management team. Unlike other financial reports, this data is not shared with shareholders, lenders and other external parties.

History

Management accounting is not a new technique. In fact, it was first put into practice in the late 1800s during the Industrial Revolution. At that time in history, the majority of businesses were owned by a small group of industrialists. Unlike the current practice of reviewing a firm’s credit history, loans and investments were made based upon personal relationships. This eliminated the need for highly detailed financial reporting. The turn of the century, however, soon brought an end to this practice. With the dawn of 1900 came new federal taxes. These were accompanied by governmental regulatory agencies, as well as an emergent financial market. New competition meant that more business was conducted with strangers than ever before. As a result, businesses were required to develop more elaborate financial reporting methods to obtain capital.

Management Accounting Reports

All management accounting reports typically consist of the same data, regardless of company or industry. Perhaps most essential is the inclusion of a firm’s current cash holdings. This information tells management exactly how much money they have to work with. Management accounting reports also include an up-to-date appraisal of accounts payable and receivable activities, a valuation of raw and in-production inventory and a list of any outstanding debts. Industry trends and forecasts may also be provided in this document.

The Institute of Management Accountants is a professional association that has provided educational support to professionals in this industry since 1919. In addition to facilitating training and networking opportunities, the organization offers a credential -- the Certified Management Accountant (CMA) -- to those who meet specific requirements. The CMA is recognized by the financial industry. The CMA credential is granted to professionals who successfully complete an examination. The test is comprised of two parts. The first section, entitled “Financial Planning, Performance and Control,” covers planning, budgeting, cost management and ethics. The second portion, “Financial Decision Making,” focuses on statement analysis, investment decisions and corporate finance.

Sustainability Reporting

What is Sustainability Reporting?

A Sustainability report is an organizational report that gives information about economic, environmental, social and governance performance.

Sustainability reporting is the practice of measuring, disclosing, and being accountable to internal and external stakeholders for organizational performance towards the goal of sustainable development. ‘Sustainability reporting’ is a broad term considered synonymous with others used to describe reporting on economic, environmental, and social impacts (e.g., triple bottom line, corporate responsibility reporting, etc.). A sustainability report should provide a balanced and reasonable representation of the sustainability performance of a reporting organization – including both positive and negative contributions.

Why companies and other organisation make Sustainability Reporting

Reporting on sustainability performance is an important way for organizations to mannge thier impact on sustainability development. The challanges of sustainability development are many, and it is widely accepted that organisation have not only a responsibility but also a great ability to exert positive change on the state of the world's economy, environmental and social conditions.

Reporting leads to improved sustainable development outcomes because it allows organizations to measure, track, and improve their performance on specific issues. Organizations are much more likely to effectively manage an issue that they can measure. By taking a proactive role to collect, analyse , and report those steps taken by the organization to reduce potential business risk, companies can remain in control of the message they want delivered to its shareholders. Public pressure has proven to be a successful method for promoting Transparency (behaviour) and disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions and social responsibilities

As well as helping organizations manage their impacts, sustainability reporting promotes transparency and accountability. This is because an organization discloses information in the public domain. In doing so, stakeholders (people affected by or interested in an organization’s operations) can track an organization’s performance on broad themes — such as environmental performance — or a particular issue — such as labor conditions in factories. Performance can be monitored year on year or can be compared to other similar organizations.

A Sustainability report is an organizational report that gives information about economic, environmental, social and governance performance.

Why companies and other organisation make Sustainability Reporting

Reporting on sustainability performance is an important way for organizations to mannge thier impact on sustainability development. The challanges of sustainability development are many, and it is widely accepted that organisation have not only a responsibility but also a great ability to exert positive change on the state of the world's economy, environmental and social conditions.

Reporting leads to improved sustainable development outcomes because it allows organizations to measure, track, and improve their performance on specific issues. Organizations are much more likely to effectively manage an issue that they can measure. By taking a proactive role to collect, analyse , and report those steps taken by the organization to reduce potential business risk, companies can remain in control of the message they want delivered to its shareholders. Public pressure has proven to be a successful method for promoting Transparency (behaviour) and disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions and social responsibilities

As well as helping organizations manage their impacts, sustainability reporting promotes transparency and accountability. This is because an organization discloses information in the public domain. In doing so, stakeholders (people affected by or interested in an organization’s operations) can track an organization’s performance on broad themes — such as environmental performance — or a particular issue — such as labor conditions in factories. Performance can be monitored year on year or can be compared to other similar organizations.

Why are the GRI the most-used guidelines and how are they created?

"The Global Reporting Initiative is the steward of the most widely used reporting framework for performance on human rights, labor, environmental, anti-corruption, and other corporate citizenship issues. The GRI framework is the most widely used standardized sustainability reporting framework in the world.”[3]

The Guidelines are the most used, credible, and trusted framework largely because of the way they have been created: through a multi-stakeholder, consensus-seeking approach.

This means that representatives from a broad cross section of society — business, civil society, labor, accounting, investors, academics, governments, and others — from all around the world come together and achieve consensus on what the Guidelines should contain. Having multiple stakeholders ensures that multiple needs and all stakeholders are considered. This contrasts to what might happen if, for example, just business representatives or just NGO representatives created the guidelines. It is also beneficial as it helps to increase the chances that all relevant sustainability issues are included, and the accompanying best measures are developed.

[edit]About the G3 and the Reporting Framework

The G3 are the so-called “Third Generation” of the GRI’s Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. They were launched in October 2006 at a large international conference that attracted thousands.

There is a “third generation” because the GRI seeks to continually improve the Guidelines. The G3 build on the G2 (released in 2002), which in turn are an evolution of the initial Guidelines, which were released in 2000.

The G3 Guidelines provide universal guidance for reporting on sustainability performance. This means they are applicable to small companies, large multinationals, public sector, NGOs and other types of organizations from all around the world. It is the way that the Guidelines are created (through the multi-stakeholder, consensus seeking approach) that enables them to be so broadly applicable.

The G3 consist of principles and disclosure items (the latter includes performance indicators). The principles help reporters define the report content, the quality of the report, and give guidance on how to set the report boundary. Principles include those such as materiality, stakeholder inclusiveness, comparability and timeliness. Disclosure items include disclosures on management of issues, as well as performance indicators themselves (e.g. “total water withdrawal by source”).

The G3 are the base of the Reporting Framework. There are other elements such as Sector Supplements and National Annexes that respond to the needs of specific sectors, or national reporting requirements. The Reporting Framework (including the G3) is a free and public good.

[edit]Global Reporting Initiative and the environment

[edit]Environmental reporting guidelines

The GRI aims to harmonise reporting standards for all organizations, of whatever size and geographical origin,[4] on a range of issues with the aim of elevating the status of environmental reporting with that of, for example, financial auditing.[5] Environmental transparency is one of the main areas of business under the scope of the GRI. As outlined in this section the GRI encourages participants to report on their environmental performance using specific criteria. The standardised reporting guidelines concerning the environment are contained within the GRI Indicator Protocol Set. The Performance Indicators (PI) includes criteria on energy, biodiversity and emissions. There are 30 environmental indicators ranging from EN1 (materials used by weight) to EN30 (total environmental expenditures by type of investment).[6]

[edit]GRI and environmental governance

The GRI is an example of an organisation that acts outside of the top-down power command structures associated with government (e.g., quasi-autonomous bodies and regulators). Environmental governance is a term used to describe the multifaceted and multilayered nature of ‘governing’ the borderless and state-indiscriminate natural environment.[7] Unlike major protected policy areas such as finance or defence, the environment requires sovereign states to sign up to treaties and multilateral agreements in order to coordinate action. Sustainability reporting is a more recent concept that encourages businesses and institutions to report on their environmental performance.[8]

Sustainable reporting is, by definition, a way in which organisations assess their own environmental accomplishments and failings, reflect on this performance and subsequently transfer this information into the public domain. This broad concept has been theoretically termed ‘reflexive environmental law’ by some academics. Reflexive environmental law is an approach in which industry is encouraged to ‘self-reflect’ and ‘self-criticise’ the environmental externalities that result as a product of their activity, and thus act on these negative social impacts in a way that dually safeguards growth and protects the environment.[9] There is also concern that the “exponential demand for disclosure”, as described by Park et al. 2008, undermines the legitimacy and prestige of the GRI. It is, in other words, operating in a saturated market counting on businesses to volunteer their information to competing agencies. More recent organisations include the Carbon Disclosure Project which has similar aims.[10]

[edit]The importance of the GRI in a globalising world

The collapse of the USSR and the augmentation of capitalist economic systems in Eastern Europe and more recently in ostentatiously self-styled ‘communist’ countries like China, coined “bamboo capitalism”,[11] suggests that this system of economic governance is likely to shape the world economy in the foreseeable future. Proponents of ‘sustainable capitalism’ or ‘conscious capitalism’[12] would conclude that organisations like the GRI effectively reconcile capitalism and the environment in an otherwise disjointed world. They concede that capitalism is not currently congruous with environmental aims, but it can be modestly redesigned where an emphasis on the GRI and its counterparts play a bigger, more innate role in business reporting.[13] However, academic criticisms of sustainable reporting in a capitalist context abound. Moneva et al. (2006) suggest that many organisations that subscribe to the GRI’s voluntary reporting regime do not improve their performance and can often manipulate the guidelines just to appear more transparent.[14]

[edit]Governance of the GRI

The “GRI” refers to the global network of many thousands worldwide that create the Reporting Framework, use it in disclosing their sustainability performance, demand its use by organizations as the basis for information disclosure, or are actively engaged in improving the standard.

The network is supported by an institutional side of the GRI, which is made up of the following governance bodies: Board of Directors, Stakeholder Council, Technical Advisory Committee, Organizational Stakeholders, and a Secretariat. Diverse geographic and sector constituencies are represented in these governance bodies. The GRI headquarters and Secretariat is in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Benefits of Sustainability Reporting

• Marketer: Improving branding and transparency with advanced reporting. Companies that fall into this category are either early in their sustainability maturity or just do what they have to do when it comes to regulatory compliance.

However, in common is that marketers use sustainability primarily to drive more awareness and transparency, which has a positive side effect on the company's branding and positioning. IT's role is helping to gather and report non-financial information, but these companies drive sustainability principally from their marketing and CSR departments.

• Transformer: Improving the bottom line with positive sustainability impacts. Companies in this category go further and use sustainability as a lever for increasing operational efficiency.

Lower energy consumption decreases both costs and carbon footprint. Hence, sustainability for these companies is seen as an opportunity to lower a company's cost base. IT is helping to identify opportunities to reduce costs, but is object of own improvement too.

Companies in this category are driving sustainability investments on an enterprise-wide basis, driven by the management of lines-of-business and owners of key processes like supply chain and real estate.

• Innovator: Improving the top line with a sustainable portfolio approach. Companies that fall into this category are the most mature, and have shifted their approach from cost to revenue.Innovators are looking to improve their top-line through a sustainable product/services portfolio approach to differentiate better in their existing markets or enter new ones. IT is helping here not only to design and produce greener products from scratch, but also to better manage the entire portfolio via integrated analytics and dashboards. The Boards and executive officers of companies in this category are pushing sustainability strategy from the top of the organization.

- Improved financial performance — there is a growing body of evidence which links financial and social performance of companies (According a CPA Australia report there is a correlation between sustainability reporting and low probability of corporate distress).

- Improved stakeholder relationships – the continuing engagement with various interest groups builds trust and improves communication.

- Improved risk management — this is a very important benefit brought about by a better understanding of non-financial material risks. Understanding risks and dealing with those risks appropriately saves companies time, money and avoids loss of reputation.

- Improved investor relationships — due to the growing demand for ethical investment funds, particularly but not limited to, by superannuation funds.

- Identification of new markets and/or business opportunities — this is a particular welcomed side effect of improved relationships with interest groups.

Auditing in accounting

What is Auditing?

Auditing has many definition, but in the business and accounting terminology it is called Financial Auditing. A financial auditing is an accounting process. Independent bodies called the auditors are used to examine an entities financial transactions and financial statements. Its major purpose is to accurately account a company’s financial transaction. The process is being made to ensure that the entity is trading fairly and in accordance with the Accounting Standards so as their issued financial statements will not be misleading for users.

Auditing is one board exam subject in the Philippine CPA board exam. The subject is not taken as a whole but it is split into two different board subjects which are the Auditing Problems and the Auditing Theory. Each is taken into account independently.

Auditing has many definition, but in the business and accounting terminology it is called Financial Auditing. A financial auditing is an accounting process. Independent bodies called the auditors are used to examine an entities financial transactions and financial statements. Its major purpose is to accurately account a company’s financial transaction. The process is being made to ensure that the entity is trading fairly and in accordance with the Accounting Standards so as their issued financial statements will not be misleading for users.

Auditing is one board exam subject in the Philippine CPA board exam. The subject is not taken as a whole but it is split into two different board subjects which are the Auditing Problems and the Auditing Theory. Each is taken into account independently.

Types Of Auditors

There are three types of auditors: internal, governmental, and external (i.e., independent auditors or certified public accountants). Internal auditors are employees of the organization whose activities are being examined and evaluated during an independent audit. The primary purposes of internal auditing are to review and assess a company's policies, procedures, and records and to review and assess a company's performance given its plans, policies, and procedures. Therefore, internal auditors review financial records and accounting systems, assess compliance with company policies, evaluate the efficiency of company operations, and assess the attainment of company goals.

Governmental auditors include accountants employed by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO). The GAO serves as the accounting and auditing branch of Congress. These governmental accountants perform accounting and auditing tasks for the entire federal government. In addition, most states have their own accounting and auditing agencies, which resemble the GAO. Because the GAO and its state counterparts are separate agencies from the departments and agencies they audit, they are similar to external auditors. Consequently, federal and state departments and agencies often have their own internal auditors, who provide internal auditing services similar to those described above. Moreover, GAO auditing largely has the same focus as internal auditing: examining financial records, assessing compliance with laws and regulations, reviewing efficiency of operations, and evaluating the achievement of objectives.

In contrast, the independent auditor is not an employee of the organization being audited or an employee of the government. He or she performs an examination with the objective of issuing a report containing an opinion on a client's financial statements. The attest function of external auditing refers to the auditor's expression of an opinion on a company's financial statements. Generally, the criteria for judging an auditor's financial statements are generally accepted accounting principles. The typical independent audit leads to an attestation regarding the fairness and dependability of the statements. This is communicated to the officials of the audited entity in the form of a written report accompanying the statements.

Investors and lenders are the primary users of financial statements and they rely on financial statements to make decisions such as whether to buy stocks or bonds, lend money, and extend credit. By conducting audits, external auditors make financial statements consistent and meaningful. To assess a company's position accurately, investors and lenders need credible financial information on a company's sales, profits, debt, value, and so forth. Companies usually have their own accountants and managers prepare their financial information, which could bring about a conflict of interest. Hence, users of financial statements demand the services of independent auditors to verify the accuracy of company information and lend credibility to the financial information, which is called attestation. Since individual users cannot verify information contained in financial statements, auditing by external accountants reduces the number of mistakes in financial statements and prevents companies from issuing fraudulent statements. In addition, the Auditing Standards Board in 1997 issued its statement "Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit," which requires greater effort on the part of external auditors to ensure that financial statements are free from fraud and misstatements.

Internal auditors also perform financial statement audits, operational audits (which are also referred to as performance auditing and management auditing), and compliance audits, although their audits have a different scope and their reports a different purpose. Because of the potential for conflicts of interest, internal auditors perform financial statement audits for internal use only. Nevertheless, much of the work internal auditors do is similar to the work external auditors do, except that it is not intended for external use. In addition, an operational audit involves reviewing an organization's activities to evaluate performance, attainment of business goals, and efficient use of resources. Internal auditors also perform compliance audits to ensure conformity with company policies as well as with applicable government laws and regulations. Even though internal auditors are employees of the companies they audit, they nevertheless strive for independence insofar as possible.

In planning the audit, the auditor develops an audit program that identifies and schedules audit procedures that are to be performed to obtain the evidence. The auditor must be aware of potential problems involved in the auditing process, such as whether company property and debt actually exist or whether company transactions actually took place. In addition, the auditor usually formulates a hypothesis about company financial information at this step, such as "Company financial reports are accurate" or "Company financial reports are inaccurate." Audit evidence is proof obtained to support these hypotheses and ultimately the audit's conclusions.

After the planning is completed, the auditor must collect the evidence necessary to support the audit's conclusions. Evidence-gathering procedures include observation, confirmation, calculations, analysis, inquiry, inspection, and comparison. An audit trail is a chronological record of economic events or transactions that have been experienced by an organization. The audit trail enables an auditor to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of internal controls, system designs, and company policies and procedures. The auditor must evaluate the initial hypothesis based on the evidence and accept or reject the hypothesis as a result. Finally, the auditor prepares a report based on the findings of the other steps, which involves making a decision about company records and claims and whether the actual evidence supports company records and claims.

Various audit opinions are defined by the AICPA's Auditing Standards Board as follows:

Investors should examine the auditor's report for citations of problems such as debt-agreement violations or unresolved lawsuits." Going concern" ' references can suggest that the company may not be able to survive as a functioning operation. If an "except for" statement appears in the report the investor should understand that there are certain problems or departures from generally accepted accounting principles in the statements that question whether the statements present fairly the company's financial statements and that will require the company to resolve the problem or somehow make the accounting treatment acceptable.

In contrast to the standardized report of external auditors, internal and governmental auditors prepare a variety of reports that serve a variety of purposes, depending on the auditing assignment and goals. Both internal and governmental reports strive to communicate information clearly and concisely. Government reports tend to emphasize the efficient use of resources by the government departments being audited, whereas internal reports tend to vary greatly because of the plethora of interests and purposes companies may have for auditing.

There are three types of auditors: internal, governmental, and external (i.e., independent auditors or certified public accountants). Internal auditors are employees of the organization whose activities are being examined and evaluated during an independent audit. The primary purposes of internal auditing are to review and assess a company's policies, procedures, and records and to review and assess a company's performance given its plans, policies, and procedures. Therefore, internal auditors review financial records and accounting systems, assess compliance with company policies, evaluate the efficiency of company operations, and assess the attainment of company goals.

Governmental auditors include accountants employed by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO). The GAO serves as the accounting and auditing branch of Congress. These governmental accountants perform accounting and auditing tasks for the entire federal government. In addition, most states have their own accounting and auditing agencies, which resemble the GAO. Because the GAO and its state counterparts are separate agencies from the departments and agencies they audit, they are similar to external auditors. Consequently, federal and state departments and agencies often have their own internal auditors, who provide internal auditing services similar to those described above. Moreover, GAO auditing largely has the same focus as internal auditing: examining financial records, assessing compliance with laws and regulations, reviewing efficiency of operations, and evaluating the achievement of objectives.

In contrast, the independent auditor is not an employee of the organization being audited or an employee of the government. He or she performs an examination with the objective of issuing a report containing an opinion on a client's financial statements. The attest function of external auditing refers to the auditor's expression of an opinion on a company's financial statements. Generally, the criteria for judging an auditor's financial statements are generally accepted accounting principles. The typical independent audit leads to an attestation regarding the fairness and dependability of the statements. This is communicated to the officials of the audited entity in the form of a written report accompanying the statements.

Investors and lenders are the primary users of financial statements and they rely on financial statements to make decisions such as whether to buy stocks or bonds, lend money, and extend credit. By conducting audits, external auditors make financial statements consistent and meaningful. To assess a company's position accurately, investors and lenders need credible financial information on a company's sales, profits, debt, value, and so forth. Companies usually have their own accountants and managers prepare their financial information, which could bring about a conflict of interest. Hence, users of financial statements demand the services of independent auditors to verify the accuracy of company information and lend credibility to the financial information, which is called attestation. Since individual users cannot verify information contained in financial statements, auditing by external accountants reduces the number of mistakes in financial statements and prevents companies from issuing fraudulent statements. In addition, the Auditing Standards Board in 1997 issued its statement "Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit," which requires greater effort on the part of external auditors to ensure that financial statements are free from fraud and misstatements.

TYPES OF AUDITS

Major types of audits conducted by external auditors include the financial statements audit, the operational audit, and the compliance audit. A financial statement audit (or attest audit) examines financial statements, records, and related operations to ascertain adherence to generally accepted accounting principles, meaning that the audit determines whether companies have followed the financial reporting standards given by various sanctioning boards such as the Financial Accounting Standards Board. An operational audit examines an organization's activities in order to assess performances and develop recommendations for improved use of business resources. A compliance audit has as its objective the determination of whether an organization is following established procedures or rules. Auditors also perform statutory audits, which are performed to comply with the requirements of a governing body, such as a federal, state, or city government or agency.Internal auditors also perform financial statement audits, operational audits (which are also referred to as performance auditing and management auditing), and compliance audits, although their audits have a different scope and their reports a different purpose. Because of the potential for conflicts of interest, internal auditors perform financial statement audits for internal use only. Nevertheless, much of the work internal auditors do is similar to the work external auditors do, except that it is not intended for external use. In addition, an operational audit involves reviewing an organization's activities to evaluate performance, attainment of business goals, and efficient use of resources. Internal auditors also perform compliance audits to ensure conformity with company policies as well as with applicable government laws and regulations. Even though internal auditors are employees of the companies they audit, they nevertheless strive for independence insofar as possible.

AUDITING STANDARDS

The auditing process is based on standards, concepts, procedures, and reporting practices, primarily imposed by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). While these standards and procedures constitute the foundation of auditing for all three types of auditors, other organizations such as the Institute of Internal Auditors and the General Accounting Office impose their own standards and procedures, which apply to internal auditing and governmental auditing, respectively. The auditing process relies on evidence, analysis, conventions, and informed professional judgment. General standards are brief statements relating to such matters as training, independence, and professional care. AICPA general standards are:- The examination is to be performed by a person or persons having adequate technical training and proficiency as an auditor.

- In all matters relating to the assignment, an independence in mental attitude is to be maintained by the auditor or auditors.

- Due professional care is to be exercised in the performance of the examination and the preparation of the report.

- The work is to be adequately planned and assistants, if any, are to be properly supervised.

- There is to be a proper study and evaluation of the existing internal control as a basis for reliance thereon and for the determination of the resultant extent to which auditing procedures are to be restricted.

- Sufficient competent evidential matter is to be obtained through inspection, observation, inquiries, and confirmation to afford a reasonable basis for an opinion regarding the financial statements under examination.

- The report shall state whether the financial statements are presented in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles.

- The report shall state whether such principles have been consistently observed in the current period in relation to the preceding period.

- Informative disclosures to the financial statements are to be regarded as reasonably adequate unless otherwise stated in the report.

- The report shall contain either an expression of opinion regarding the financial statements, taken as a whole, or an assertion to the effect that an opinion cannot be expressed. When an overall opinion cannot be expressed, the reasons therefore should be stated. In all cases where an auditor's name is associated with financial statements, the report should contain a clear-cut indication of the character of the auditor's examination, if any, and the degree of responsibility he or she is taking.

THE AUDITING PROCESS

Auditors generally conduct audits following four general steps: planning, gathering evidence, evaluating evidence, and issuing a report.In planning the audit, the auditor develops an audit program that identifies and schedules audit procedures that are to be performed to obtain the evidence. The auditor must be aware of potential problems involved in the auditing process, such as whether company property and debt actually exist or whether company transactions actually took place. In addition, the auditor usually formulates a hypothesis about company financial information at this step, such as "Company financial reports are accurate" or "Company financial reports are inaccurate." Audit evidence is proof obtained to support these hypotheses and ultimately the audit's conclusions.

After the planning is completed, the auditor must collect the evidence necessary to support the audit's conclusions. Evidence-gathering procedures include observation, confirmation, calculations, analysis, inquiry, inspection, and comparison. An audit trail is a chronological record of economic events or transactions that have been experienced by an organization. The audit trail enables an auditor to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of internal controls, system designs, and company policies and procedures. The auditor must evaluate the initial hypothesis based on the evidence and accept or reject the hypothesis as a result. Finally, the auditor prepares a report based on the findings of the other steps, which involves making a decision about company records and claims and whether the actual evidence supports company records and claims.

AUDIT REPORTS

The independent audit report sets forth the independent auditor's opinion regarding the financial statements. The auditor's opinion indicates whether the financial statements are fairly presented in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles, and applied on a basis consistent with that of the preceding year (or in conformity with some other comprehensive basis of accounting that is appropriate for the entity). A fair presentation of financial statements is generally understood by accountants to refer to whether:- The accounting principles used in the statements have general acceptability.

- The accounting principles are appropriate in the circumstances.

- The financial statements are prepared so they can be used, understood, and interpreted.

- The information presented in the financial statements is classified and summarized in a reasonable manner.

- The financial statements reflect the underlying events and transactions in a way that presents the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows within reasonable and practical limits.

Various audit opinions are defined by the AICPA's Auditing Standards Board as follows:

- Unqualified opinion: An unqualified opinion states that the financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows of the business in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles.

- Explanatory language added to the auditor's standard report: Circumstances may require that the auditor add an explanatory paragraph (or other explanatory language) to the report.

- Qualified opinion: A qualified opinion states that, except for the effects of the matter(s) to which the qualification relates, the financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows of the business in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles.

- Adverse opinion: An adverse opinion states that the financial statements do not represent fairly the financial position, results of operations, or cash flows of the business in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles.

- Disclaimer of opinion: A disclaimer of opinion states that the auditor does not express an opinion on the financial statements.

Investors should examine the auditor's report for citations of problems such as debt-agreement violations or unresolved lawsuits." Going concern" ' references can suggest that the company may not be able to survive as a functioning operation. If an "except for" statement appears in the report the investor should understand that there are certain problems or departures from generally accepted accounting principles in the statements that question whether the statements present fairly the company's financial statements and that will require the company to resolve the problem or somehow make the accounting treatment acceptable.

In contrast to the standardized report of external auditors, internal and governmental auditors prepare a variety of reports that serve a variety of purposes, depending on the auditing assignment and goals. Both internal and governmental reports strive to communicate information clearly and concisely. Government reports tend to emphasize the efficient use of resources by the government departments being audited, whereas internal reports tend to vary greatly because of the plethora of interests and purposes companies may have for auditing.

LEGAL RESPONSIBILITIES

The legal responsibilities of the auditor are determined primarily by the following:- Specific contractual obligations undertaken.

- Statutes and common law governing the conduct and responsibilities of public accountants.

- Rules and regulations of voluntary professional organizations.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)